How the motion comes into Animation

“The frequency at which frames in a television

picture, film, or video sequence are displayed.” This is how our good friend

Google defines Framerates. These are generally measured in frames per second,

or FPS for short.

Now avid Gamers will probably be very familiar

with that term, as higher framerates were and still are one of the main reasons

PC users declare their system superior to consoles, calling them filthy console

plebeians while honoring themselves with the title of the glorious

PC-Masterrace.

But as the title suggests, we aren’t here to

discuss the antics and to comment on that odd fight that takes place inside the

community of gaming. So, let's discuss

the promised topic: How does the motion come to be in TV-produced anime?

The short answer is: it’s the result of the

hard work of many different people. On that account let's take a quick dive into the production of anime, or precisely

which staff members are involved in creating the animation for anime.

The production of anime is usually split up

into three different stages: The Pre-Production, the In-Production, and the Post-Production. The animation is most logically made during the

In-Production phase. The staff members who have the task to create the

animation are the key animator, the animation director, and the inbetweener.

The In-Production-Stage in anime is the Stage

during which the anime itself is produced, is arguably the most important step

while producing an anime. Without it one wouldn’t have a finished product.

During this stage the script is written, the

Storyboards are made, the layout is begin designed and finally the animation

will be produced.

The episode script is written as a first part

of the Production of the series itself. Episode scrips usually elaborate on the

series script and selects what exactly is shown during the episode, as well as

all the dialogues. The script is either written by a collective or a single

person, which is then revised by other members of the Production staff, notably

the series director, the episode director and the producers. In many cases a

script is re-written three to four times before being finalized. However,

modifications to the script past this stage are very rare.

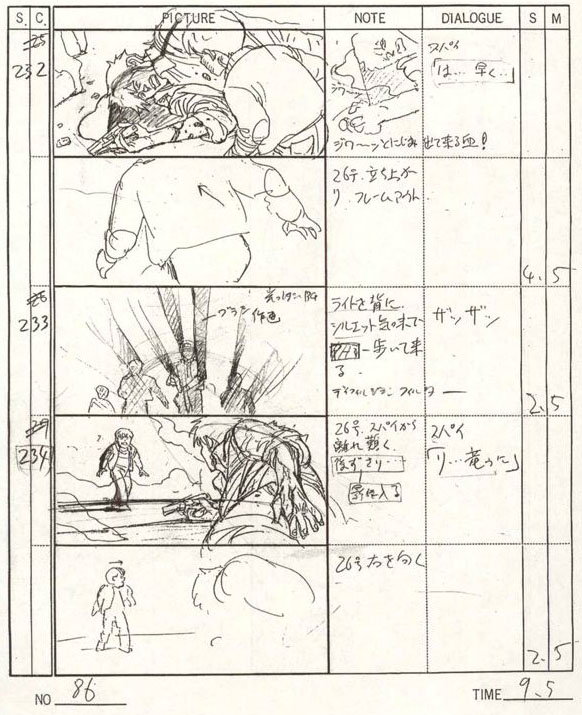

Next in comes the creation of the Storyboard, which

is the first kind of drawing realized for an animation. The storyboard is

essentially the translation from the script to images, although they resemble

to rough sketches. If the storyboard is created by an episode Director himself,

then this often implies that the episode is truly the vision of the director.

In TV-productions, this is rarely the case, so the Storyboards are handled by a

special credit, the Storyboarders.

|

| Storyboard from the 1988 movie "Akira" by Katsuhiro Otomo |

They are usually drawn on A4 paper by hand and

contain the core information of how the episode and all its different scenes

look. The Storyboard divides the episode up into scenes and then further into

individual cuts (or Shots) that comprise the scene. Each Shot is given a number

as well as details on what’s inside the frame, character and camera movements

(such as zooms or panning’s), as well as notes on what kind of background art

will be visible, additionally the dialogue as well as the length of each shot,

measured in frames per second.

It takes about three weeks for a Storyboard to

reach completion.

|

| Layout from the Ghibli movie "Princess Mononoke" |

Next up is the lesser-known layout stage. This

time every single shot from the storyboard is redrawn in greater detail, as it

will be seen on the TV broadcast. The shots from the cuts are upscaled to the full-sized

animation papers, additional details regarding camera movement are also added,

creating basically a blueprint of each shot. The basic structure of the Background

art is added in (i.e. a tree there and a mountain there) as well.

After being approved by the director, these

layouts are then duplicated and given to the background department (who get the

originals), and the key animators. The art director and assistants work on

painting the background artwork based on the rough drawings of the layouts

while the rest of the production process continues concurrently.

After being approved by the director, these

layouts are then duplicated and given to the background department (who get the

originals), and the key animators. The art director and assistants work on

painting the background artwork based on the rough drawings of the layouts

while the rest of the production process continues concurrently.

By this stage, the look of every shot is

clear-cut, from the position of the character’s, to camera motion to the

background-art. Next in order the stage when the actual movements are added to

the Animation.

The key animators are the ones who will draw

the structure of a frame, meaning they will only draw the parts of a cut which

are the most important. Let’s look a quick example: When animating a punch, the

key animator will then draw the fist flying,

next the first hitting its target and finally the impact of the punch (if it's a strong one). Key Animators are mostly

older and more experienced animators, they are also the ones who have the most

creative freedom during the whole process. While they are restricted to use

pre-defined Character designs, camera angles and composition (which are defined

by the storyboard), how exactly the movement or the scene looks is up to the

individual key animator. This way some animators were able to develop their own

style of animating which can even be recognized by some people.

The key animators are the ones who will draw

the structure of a frame, meaning they will only draw the parts of a cut which

are the most important. Let’s look a quick example: When animating a punch, the

key animator will then draw the fist flying,

next the first hitting its target and finally the impact of the punch (if it's a strong one). Key Animators are mostly

older and more experienced animators, they are also the ones who have the most

creative freedom during the whole process. While they are restricted to use

pre-defined Character designs, camera angles and composition (which are defined

by the storyboard), how exactly the movement or the scene looks is up to the

individual key animator. This way some animators were able to develop their own

style of animating which can even be recognized by some people.

Additionally, when discussing animators, I just

feel obligated to mention Yukata Nakamura, also known as the grandmaster of Battle anime. Because of his fame, Nakamura is even allowed to storyboard

his own scenes, giving his work has a very distinct feel of momentum and

epicness, which demonstrates his deep understanding of cinematography.

If you want to know what a cut from Yukata Nakamura looks like, search no further than Fullmetal Alchemist Brotherhood. The second opening was his work. He is also known to have contributed in major parts to other big hit titles from the Animation Studio Bones, like Space Dandy and Kekkai Sensen (Blood Blockade Battlefront). The final battle in Sword of the Stranger (also a Bones production) is regarded till today as one of the best sword fights to have ever been animated, and of course, the fight is entirely choreographed and animated by Yukata Nakamura.

epicness, which demonstrates his deep understanding of cinematography.

If you want to know what a cut from Yukata Nakamura looks like, search no further than Fullmetal Alchemist Brotherhood. The second opening was his work. He is also known to have contributed in major parts to other big hit titles from the Animation Studio Bones, like Space Dandy and Kekkai Sensen (Blood Blockade Battlefront). The final battle in Sword of the Stranger (also a Bones production) is regarded till today as one of the best sword fights to have ever been animated, and of course, the fight is entirely choreographed and animated by Yukata Nakamura.

|

| Top: Key Animation for "Space Dandy" Middle: Yutapon-Cubes in the second Season of "My Hero Academia" Bottom: Key Animation by Yukata Nakamura for the movie "Sword of the Stranger" |

Another, nearly equally important Animator is Yoshimichi Kameda, whose animation style is just as easy to recognize. His work consists of heavy black and brushy paint strokes, thus giving his cuts a distinct ruff, erratic and wild feeling.

He is known to have worked with Industry

Legends like Hideaki Anno on certain

shots in Evangelion 3.0 as well as the critically acclaimed Fullmetal Alchemist

Brotherhood. He is responsible for creating some of the best-looking action sequences in the series, one of them being the

death-scene of Lust in episode 19 respectively Envy's death-scene in episode 54.

Additionally, he worked on some of the most

memorable fights in One Punch Man, one them being the Underdweller-fight, of which he animated the beginning and the

middle sequences.

Yoshimichi Kameda is of the, if not the leading

force behind the Anime adaptation of the Mob Psycho 100 manga, creating the

Character designs and handling a major part of the animations.

Envy's Death, Ep. 54 from Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood

Now we got set off-track speaking about two notorious animators, let’s continue where we left off:

Obviously Key animators they aren’t the only

ones who bring movement to still images. As I stated before Key animators

usually only draw the most important frames in a cut, so looking at their work isolated

the movements would simply jump from one position to the next, without any actual

fluidity in the movement. Here’s when the in-between animation comes into play.

The in-between animators create the missing movements between keyframes, in essence,

they fill in the gaps. Since in-between animation is basically grunt work it is

either outsourced (mostly to Korea) or it becomes the task of less experienced

animators, which is also paid accordingly

bad.

A single episode of anime usually needs about

20 different key animators and even more in-between animators to be made. When

so many different people are drawing the same stuff, someone must worry about

consistency. That someone is the Animation Director. Animation directors tend

to be more experienced animators and are paid more for the role. However, it is

their responsibility if things go wrong with the animation, making it a

potentially very stressful job, especially under time pressure. Often, an

episode of anime will have more the one animation director, and this can be a

sign of scheduling problems, with more people needed to complete the episode

satisfactorily and on time, or even a sign of many poor drawings needing

correction. Furthermore, it can also be because animation directors are being

used to their respective specialties (i.e. An animation director brought on to

handle a mecha sequence, or to handle drawings of animals), or an indication

that it was a difficult and demanding episode with a lot of drawings.

Next, to the animation director, an anime Series also tends to have a Chief animation

director, who oversees the complete series. He often works a lot with the

character designer or he mans both positions.

Now that we know all there is to know about the

staff members directly responsible for the animation, we can now answer the

question (high) above.

Anime, produced for both TV and the big screen

always has a constant framerate (24 frames per second), meaning we see 24

images for every second of animation.

But most of the time anime gets produced in

2's, meaning there is a unique image

every second frame. This involves that a second of animation only consists of

12 individual images per second which are then shown twice to create a fluent

motion of 24 fps. To save time and thus money animators use all sorts of tricks

to lessen their already enormous workload.

Sometimes anime uses even less unique images

(sometimes called cell, reminiscent of the traditional way of making an animation using celluloid) in a second and will

only be animated in 4's or even 5's. A framerate this low is usually used

during dialogue or comedic scenes, where there is either not much movement or

the hasty movements of a character doesn’t

feel out of place.

An also commonly used method is to divide the

individual shot into different layers of importance which are then animated

accordingly. While the main focus of the

shot may be on the main character in the

foreground, which is animated at the standard 2's, irrelevant background motion is simultaneously animated in

3's.

Something else to know about shooting on twos

is that it makes it very easy to smooth out an animation because you can just

replace one of the duplicated drawings with a "tween" cell. If

someone makes a fast movement, shooting on twos make

it look like their arm jumped from one side of the screen to the other.

Replacing the duplicate cell with a "tween" will make the action

smoother. Plus, there's repetitive motions, reused animation, and other ways to

save drawing time/money/wear on the artists.

In conclusion the motion itself is created by showing

the eye images in quick succession, and these images are created by whole team

of people. And there are still many more steps to be made to reach a finished product from where we left off, most notably the coloring, editing and sounddesign.

ayo

ReplyDelete